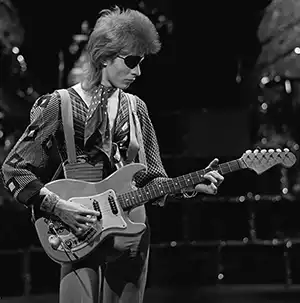

When I awoke to a New York Times push notification that David Bowie had died, I just couldn’t swipe through to read the story. Similarly, I’m struggling to find the words here to describe his enormous influence on my life. See, I was 14 in 1972, the release year of “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars,” arguably one of the most influential pop albums of all time. This means I was a “Bowie Kid” at a time when being one was daring and risky.

Even though Bowie was 11 years older, he legitimized our too-young-to-be-hippies age group as a generation unto itself, a generation rejecting hippie mellowness while embracing the disenfranchised and the taboo. When, in “All the Young Dudes,” he wrote that “brother’s stuck at home with his Beatles and his Stones,” it was interpreted by many of us as the drawing of a generational bright line: those who embraced Bowie on one side, everyone else on the other.

Hard as it might be to believe now, in those days many young people could not get past Bowie’s sexuality — the press spitefully referrred to this as his “gender-bending” — in order to enjoy the music, which not only rocked but had a breadth and depth we couldn’t fully appreciate at the time. Bowie challenging us to examine the full spectrum of sexuality, including areas that still were not widely discussed in 1972, was truly revolutionary. Not only was Bowie a hero for gay, bi and trans men and women, but liking his music helped young straights to accept and acknowledge that it was OK for their friends (or anyone, for that matter) to be gay. Indeed, in “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide,” the cathartic closer of “Ziggy Stardust,” he told all of us that being who we were was just fine — in fact, it made us “wonderful.” (“Gimme your hands cause you’re WON-DER-FUL”)

I took Bowie’s hand and he led me through artistic vistas that were clearly out of my working class comfort zone. The first time I gave a full listen to my hometown Philadelphia Orchestra was when Bowie narrated on a recording of “Peter and the Wolf,” under the baton on Eugene Ormandy. I discovered the wonders of Brecht and Weill through his recordings. And my first Broadway play was the 1980 production of “The Elephant Man,” with Bowie in the title role, at the Booth Theatre, where many in the audience knew little (and cared less) about his music. Eventually, I subscribed to the Philadelphia Orchestra, grew to appreciate the singing of Agnes Bernelle and Ute Lemper and returned to Broadway many times. All of this was in addition to being among the millions worldwide whom Bowie introduced to Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, Brian Eno, Kraftwerk and others. For me, a guy many dismissed as a glam rock star turned out to be an arts educator of sorts — he made it cool to try new things.

Amid the many remembrances and stories shared when the news hit, the most peronally significant was the phone call I receieved from my son, George, who is 18 and studies music in Philadelphia. He’s a bit of a late riser, so I’d already begun to absorb the news by the time he called in shock that Bowie had died. The call to me was the first he made. Our intergenerational grieving, based on shared and individual explorations of Bowie’s art, was something I could not have imagined happening with my own father. I honestly can’t think of a single artist we shared whose death would have merited a phone call.

As fate would have it, George and I had scheduled some errands the day Bowie’s death was announced. This put us in the car together for a few hours of what became an impromptu David Bowie tribute. We took turns selecting tracks and sharing observations. George kept returning to Bowie’s 1975 recording of Lennon and McCartney’s “Across the Universe,” which on the “Young Americans” album featured Lennon’s primal-scream backing vocals and guitar. “Did you hear that?,” George asked at one point. “It’s like he (Lennon) is trying to do his best fake David Bowie impersonation. They sound like they’re trying to crack each other up.” The thought of these two great departed artsits laughing in the studio together, and that someone 44 years removed from Ziggy would recognize it, somehow made the grieving easier.