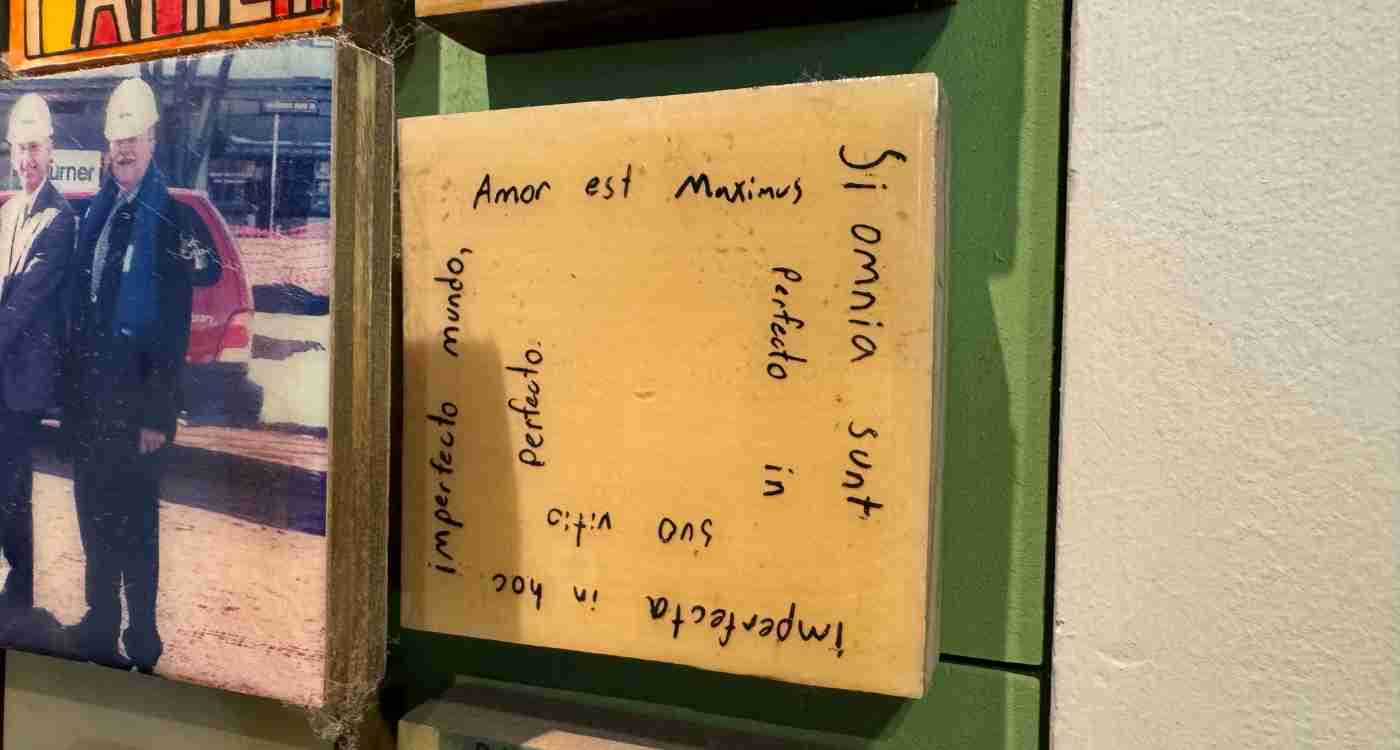

Among the plethora of languages inscribed on the tiles of the “Happy World” installation, Latin seems to blend in discreetly with the voices of so many classrooms and homes echoed in this ever appealing work of art. Featured in the image here is one of those unassuming tiles, which is easy to overlook at the periphery on the right side of the installation. Working around the tile, the following text emerges:

Si omnia sunt imperfecta in hoc imperfecto mundo, Amor est maximus perfect[us] in suo vitio perfecto.

If all things are imperfect in this imperfect world, Love is the greatest—perfect in its own perfect fault.

I’ve often wondered about this tile, as I muse over the often surprising curiosities preserved in this piece. To me it reads like the broodings of a student, and in particular of a young adult, who has discovered how powerful a force love can be in their life—in all our lives really—and finds in it a remedy to the specific ennui and world-weariness of late adolescence. There’s something timelessly right in this expression of that time of life, in which the passions are felt so strongly and without the guardedness more typical of what we cautiously call “middle age.”

Whether I’m right or wrong about the person whose voice is captured in this charming tile, one thing is unmistakeable: it preserves a piece of what scholars call “Neo-Latin”—the idiom of classicizing Latin emerging in the Italian Renaissance and continuing as a language of literature, culture, science, theology and law down to present. Latin’s great cultural signficance, which peaked in the Early Modern period, may have waned considerably over the last two centuries, as English has become the new international standard, but Latin can still play an important role for students and scholars alike. More than two millennia of history, science, and literature become accessible to students of Latin, so that it can be an enriching resource for connecting the past and present. The tiles in Latin on the “Happy World” installation can reinforce this point: in them one sees how Latin, far from a “dead” language, continues to be a meaningful resource for self-expression and communication.

A little more than a year ago, I did some research to determine which secondary schools offer a Latin curriculum of one kind or another and I learned that many schools in the Princeton area offer Latin as an area of study: in addition to Princeton High School at least 11 more schools offer some (or many) opportunities for Latin language study. This abundance of opportunity reflects the vitality of the language as an academic resource and a cultural heritage which the community’s educators continue to cherish.

Recently the library launched its own contribution to this effort, bringing forth a group of programs devoted to Latin language study. Distinctive to the library’s approach to promoting the study of Latin, each of these programs emphasizes “active Latin” or “living Latin,” as it is sometimes called—that is, a practice of Latin language study that incorporates writing, speaking and listening to the language as skills complementary to learning to read it. While there are several contrasting approaches to this way of studying the language—my own formation in active Latin comes from the University of Kentucky’s Institutum Studiis Latinis Provehendis—the curricula offering the best fit for the library’s busy programming calendar comes from the Paideia Institute. The “Living Latin” program at the library offers weekly meetings, five weeks at a time, as support for self-guided study approachable by learners in the higher secondary grades. Over two years, learners pursuing this course work through a complete introduction to the Latin language. Meanwhile, learners in the middle grades can complete “Elementa” over the course of a year—likewise committing to the course five weeks at a time—and they will enjoy a thorough introduction to the study of Latin language and to Roman history and mythology. Finally, the youngest learners in the elementary grades can pursue “Teaching Literacy with Latin,” a fun and engaging experience of Latin language study through a four-week period in October.

All of these programs strive in their way to make Latin language study even more accessible to the Princeton community and to present it in a distinctive way. Though most of these programs are now full (at the time of writing there is just one seat available in “Living Latin”), by joining the waiting list a space may be secured in the event a seat becomes available.