About this guide: The purpose of this guide is to provide insights and strategies for overcoming confusion around identifying credible information. Over the past decade, our online information landscape has been dramatically transformed. As a result, telling fact from opinion, and identifying credible journalism, has become more difficult. Whether you are a concerned citizen or an educator, this guide is for you.

Misinformation is defined as false, incomplete, inaccurate/misleading information or content which is generally shared by people who do not realize that it is false or misleading. This term is often used as a catch-all for all types of false or inaccurate information, regardless of whether referring to or sharing it was intentionally misleading.

Disinformation is false or inaccurate information that is intentionally spread to mislead and manipulate people, often to make money, cause trouble or gain influence.

Malinformation refers to information that is based on truth (though it may be exaggerated or presented out of context) but is shared with the intent to attack an idea, individual, organization, group, country or other entity.

You can learn more and explore real-world examples of each of the forms here or here.

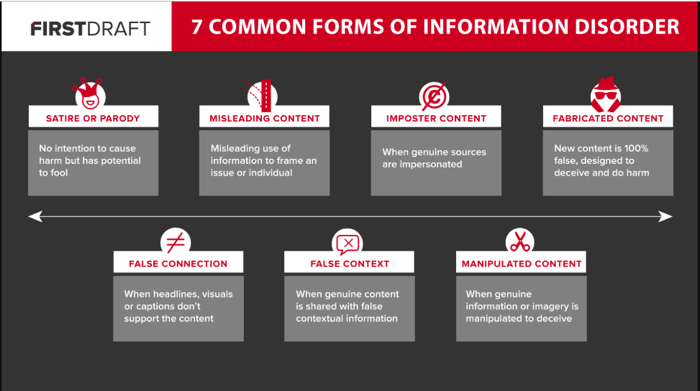

All of the above forms of problematic information are part of what has become known as “information disorder,” a term coined by journalism researchers Claire Wardle (Brown University) and Hossein Derakhshan (London School of Economics and Political Science) who were troubled by the misuse of the vague phrase, “fake news.”

Wardle cofounded First Draft News, a collaborative project to “fight misinformation and disinformation online,” whose mission continues at Information Futures Labs at Brown University. Wardle created the “7 Types of Information Disorder,” a typology that illustrates and emphasizes the types of information disorder in our media landscape, and this information disorder glossary. This typology was derived from a report commissioned by the Council of Europe.

Tips for Critically Evaluating Online Information:

Essential questions to ask when analyzing information center on the authority of the source/author and the purpose of the information:

Authority: Who wrote/sponsored it?

- Is the author an expert in the field or just someone relaying their personal experience? Is it a company or a person?

- Do they have any credentials (a degree, certification, training or extensive experience) that indicate they’ve studied the topic, worked in the field or have recognized expertise?

- Are there sources/citations referenced? Is there a way to contact the author?

Purpose: What do they want me to do with the information?

- Is the purpose to sell, persuade, entertain or inform?

- Are there words and images present that seem designed to appeal to your emotions?

- Is a political, ideological, religious or cultural point being made?

Conspiracy theories and propaganda tap into our deepest fears, emotion, and deeply held beliefs or values. Our tendency toward cognitive biases also helps to make belief in these theories immune to logic. We often wonder how any rational and logical-thinking person could believe in them, but facts don’t win arguments. If you find the tone, language or claims of a piece of information inspire visceral fear or anger, it’s a good idea to investigate the claims elsewhere by cross-referencing them with a variety of different information sources.

Watch

From PBS News Hour’s Student Reporting Labs series on misinformation, “Moments of Truth,” this conversation features David Morrill of Portland, Oregon, and his father. David Morrill was involved in conspiracy theory communities online until a mental health crisis forced him to confront his beliefs. This conversation with his father about how he found his way back to reality is illuminating and provides a compassionate model for speaking with individuals impacted by conspiratorial thinking.

AI-Manipulated, Synthetic Content

With open-source chatbot technology becoming more common, it is becoming simpler and cheaper for those with ill intentions to repurpose generative AI models for activities like voter suppression. Wealthy corporations, individuals and state-sponsored groups might train AI models to influence or dissuade voters by integrating large language models (LLMs), the foundation of generative AI chatbots, with voice or video generation technologies (“deepfakes”) to spread false information about the voting process and democratic systems. Such models could act as potent tools for disinformation, significantly boosting efforts to sway and deceive voters.

The first known instance of the deployment of voice-cloning artificial intelligence at significant scale to try to deter voters from participating in an American election came in January, 2024, when robocalls impersonating President Joe Biden went out two days before the New Hampshire primary. Creating this fake audio reportedly cost just $1 and took less than 20 minutes to produce.

In the era of generative AI and deepfakes, seeing is no longer believing. Check out the Washington Post’s “Fact Checkers’ guide to manipulated video” to learn about the three essential ways video is being altered and circulated online: footage taken out of context, deceptively edited or deliberately altered. Technology experts caution that while it may still be possible to spot a deepfake at the moment, individuals will not be able to rely on advice or tips to do so in as short as a year from now as “…artificial intelligence has been advancing with breakneck speed and AI models are being trained on internet data to produce increasingly higher-quality content with fewer flaws…”

If you determine that a claim or news story circulating online features either disinformation or AI-manipulated or synthetic content, you can and should report it. (See reporting resources below in the “reporting AI-manipulated content” section of this guide.)

Evaluating Online Information: A Toolbox

- Do not share questionable claims or any news story you see online that is suspect. The more problematic information is spread, the more it becomes driven by algorithms, increasing the likelihood of virality. Investigate the claims by …

- Searching fact-checking websites to determine if someone has already confirmed or debunked the claim. If verification is not possible, shift to lateral reading…

- Practice “Lateral Reading”: A strategy used by fact checkers for investigating who’s behind an unfamiliar source by leaving the webpage and opening a new browser tab to see what verified, trusted websites say about the unknown source.

- Dealing with a suspicious-looking image? Try reverse image searching tools: Tineye or Google’s reverse image search are the easiest, quickest tools to determine the provenance and authenticity of an image.

- Looking for a standard procedure or set of steps that encompasses all of the above? Check out the SIFT Method for evaluating information.

Selected Readings

This list identifies titles pertaining to disinformation and misinformation, two forces pervading our current political discourse and undermining our democracy’s potential to build consensus among parties with competing interests.

The following articles are recommended as well, in order to delve into specific, relevant areas of this topic:

- Countering misinformation and fake news through inoculation and prebunking (2/2021): A scholarly article by Stephan Lewandowsky (University of Bristol) and Sander van der Linden (Cambridge University); there is no paywall through this link.

- Despair underlies our misinformation crisis: Introducing an interactive tool. By Carol Graham and Emily Dobson. Commentary. Washington: The Brookings Institution, 13 July 2023.

- How partisan polarization drives the spread of fake news by Mathias Osmundsen, Michael Bang Petersen, and Alexander Bor. Tech Stream. Washington: The Brookings Institution, 13 May 2021.

- The misinformation virus: Lies and distortions don’t just afflict the ignorant. By Elitsa Dermendzhiyska. Aeon. London: Aeon Media Group, 16 April 2021.

- The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction (2022): A scholarly review by Ecker, et al published in “Nature Reviews Psychology,” offering a comprehensive overview of this topic. The authors “describe the cognitive, social and affective factors that lead people to form or endorse misinformed views, and the psychological barriers to knowledge revision after misinformation has been corrected, including theories of continued influence.” There is no paywall through this link.

Web Resources on Misinformation and Disinformation

Amanpour & Co. (PBS) “Caleb Cain and Kevin Roose on Radicalization and YouTube”: Hari Sreenivasan delves into the perils of technology with Caleb Cain and New York Times reporter, Kevin Roose, to present a real-life case study of radicalization through disinformation on YouTube.

Center for an Informed Public (University of Washington): CIP’s mission is “to resist strategic misinformation, promote an informed society, and strengthen democratic discourse.”

IREX is a global development and educational organization whose “learn to discern” approach focuses on identifying credible information for decision-making, recognizing misinformation/disinformation while alleviating the impact and spread of misleading and manipulative information.

The Network Contagion Research Institute: A project of Rutgers University, the network is an independent group whose mission it is to track, expose and combat misinformation through “empowering partners to become proactive in protecting themselves against false narratives that create rifts of distrust that impact institutions, capital markets, public health, and safety.”

Misinformation and Disinformation: A Guide for Protecting Yourself: This guide from Security.org provides learning resources about misinformation and disinformation, fact-checking tips and strategies for protecting yourself and your loved ones from misinformation and disinformation.

A Survey of expert views on misinformation: Definitions, determinants, and future of the field: This well-organized and succinct report from Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics, and Public Policy provides expert analysis on the definition of misinformation and debates surrounding it.

What Stanford research reveals about disinformation and how to address it: Research from Stanford scholars from across the social sciences on the threats disinformation poses to democracy is presented.

Websites on News Literacy and Journalism:

Ad Fontes Media is a media research organization that has created an Interactive Media Bias Chart allowing users to evaluate source bias, including the accuracy of factual and investigative reporting and political positions of their editorial writing.

Center for Cooperative Media (Montclair State University): Founded in 2012 to address the diminishing presence of local journalism in New Jersey, the center “coordinates statewide and regional reporting, connecting more than 280 local news and information providers trough its flagship project, NJ News Commons.”

Center for News Literacy from Stony Brook University School of Journalism: A curated collection of lessons, video tutorial and resources for learners of all ages from Stony Brook University. Pay careful attention to the “7 Standards of Quality Journalism.”

Core Principles of Ethical Journalism from the Ethical Journalism Network: ENJ unites “more than seventy groups journalists, editors, press owners and media support groups from across the globe.” The many diverse supporters of the group find consensus in their shared commitment to the principles of ethical journalism.

“Evaluating News Sources” and “What Makes a Trustworthy News Source” (chapters from “An Open Education Pressbook” by Mike Caulfield): This open educational resource offers tips and strategies for enhancing the ability to evaluate information online and in the news. Mike Caulfield is a research scientist at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public, where he studies the spread of online rumors and misinformation.

New Jersey Civic Information Consortium: The consortium’s mission is to “to foster increased civic engagement by providing financial resources to organizations building and supporting local news and information in communities across New Jersey, with a particular emphasis on news deserts and historically marginalized groups.”

The Poynter Institute for Media Studies has been a hub for supporting journalists in their education and professional development since its founding in 1975.

“Source Hacking: Media Manipulation in Practice” from Data & Society provides insight into several ways media manipulators spread disinformation.

For Educators

A number of engaging games for learning about disinformation are available: Bad News is an online game developed by researchers at the University of Cambridge. The imperative: See how fast you can spread fake news; Geoguesser offers the opportunity for students to identify misused images; also from Cambridge University is the Harmony Square Game, which illuminates the tactics and manipulation techniques bad actors use to mislead; and Spot the Troll was developed at the Clemson University Media Forensics Hub to grant practice with spotting fake social media accounts.

Checkology is a free e-learning platform with engaging, authoritative lessons on subjects led by experts like news media bias, misinformation, conspiratorial thinking and more. Students develop the ability to identify credible information, seek out reliable sources and apply critical thinking skills to separate fact-based content from falsehoods.

Civic Online Reasoning (from Stanford University) offers free curriculum sets (lessons, videos and assessments) for secondary level educators to help teach students how to critically evaluate digital information.

Confronting Misinformation, Disinformation and Malinformation (Facing History & Ourselves, free curriculum): A lesson plan and primer for high school educators interested in teaching students about different types of false, misleading and manipulative information, and how to avoid believing in, and sharing, such content. Resources include activities, handouts and slides.

Digital Resource Center (Center for News Literacy at Stonybrook University) is funded by the McCormick and MacArthur Foundations. It serves as a clearinghouse of materials, lesson plans, videos and professional development resources for teachers looking to enable students to learn how to “pluck reliable information from the daily media tsunami.” Check out the portal page, too, for resources specific to grade school teachers (grades 6 through 12), students, or college instructors.

Media Literacy classes in Finland teach students in fourth grade and up how to identify hoaxes, avoid scams, and debunk propaganda. This fascinating reporting from “CBS News Sunday Morning” highlights the underlying pedagogical ethos for the curriculum and Finnish students’ capacity for learning important civic skills in todays “information society.”

NewsGuard provides K-12 schools with media literacy tools and curricula aligned with Common Core & ISTE standards that enable students to develop skills to help them detect and counter misinformation. Its staff of trained journalists and information specialists throughout the world collects, updates, catalogues and tracks all of the top false narratives spreading online.” (Scroll down to check out the free resources readily offered.)

Reporting Disinformation & AI-Manipulated Content

Use the following resources to report problematic and fabricated content or information:

- AI Incident Database’s reporting tool for submitting “AI incidents” offers individuals the opportunity to report incidents of AI-created harm or potential harm which they define as “…unforeseen and often dangerous failures when they are deployed to the real world…intelligent systems require a repository of problems experienced in the real world so that future researchers and developers may mitigate or avoid repeated bad outcomes”. The database is also searchable for those looking to get a better understanding of AI-related contributors to Information Disorder.

- How to report Misinformation Online (World Health Organization): A clear and concise guide offering step-by-step instructions for reporting misinformation to 10 different social media platforms

- Microsoft: Report deceptive, AI-generated media or content encountered through Microsoft channels and products. (AI-generated misinformation related to Election 2024 is a priority.)

Fact Checking Sites and Services

BBC Disinformation Watch: A biweekly newsletter focused on the spread of misinformation and disinformation in the news includes topical deep-dives, studies and insights from leading researchers in the field.

Factcheck.org: A longstanding, and trusted project of the Annenberg Public Policy Center with a focus on national politics.

Google’s FactCheck Explorer is a tool that allows people to view and search for fact checks that have been investigated by independent organizations around the world. This tool is frequently utilized by professional fact checkers, journalists, and anyone with an interest in seeking the facts

NewsGuard’s “Reality Check”: Weekly reports updated regularly focusing on how misinformation online is undermining trust—and who’s behind it.

Politifact : Founded by the Tampa Bay Times and now operated by the Poynter Institute, PolitiFact is a nonpartisan fact-checking organization that focuses on national political figures.

Snopes dates back to 1994 by investigating “urban legends, hoaxes, and folklore.” It has evolved over time into a reliable resource for overturning misinformation with “evidence-based and contextualized analysis.”