Even if most people are not fans of insects, chances are that they tend to have a soft spot for butterflies. Perhaps this stems from memories of raising monarch butterflies in grade school, or watching them feed in a grandmother’s garden. However, despite their popularity, monarch butterflies appear to be fluttering towards extinction. According to a Smithsonian.com article, the population has declined 97 percent since 1981.

After a visit to the caterpillar terrarium at Duke Farms, my partner and I became interested in trying to raise monarch caterpillars into butterflies. Enamored by their personalities, and curious about their growth, raising monarchs was an easy way for us to have temporary pets, learn about nature, and help our local ecosystem.

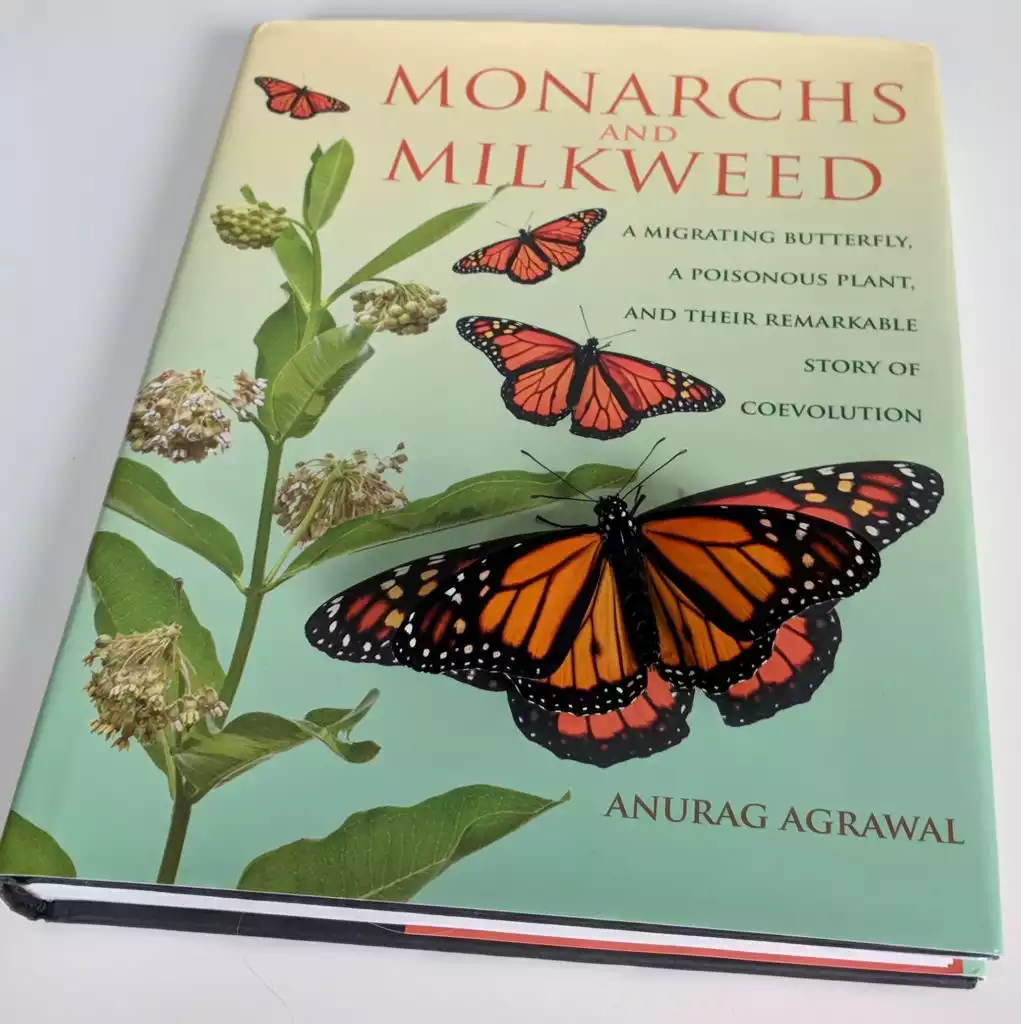

Of course, as a librarian, half the fun of a project like this comes from researching the process as well as watching it. Anurag Agrawal’s book, “Monarchs and Milkweed,” which was published last year by Princeton University Press, has to be my favorite book about monarchs. It delves into many aspects of monarch and milkweed coevolution, and is punctuated with fresh anecdotes about working with the creatures in Cornell University’s lab, and also has a sense of humor.

Many butterfly hobbyists post online. Instagram, along with Youtube, became my main sources. Following popular tags on Instagram, I could see how other people set up their own monarch habitats, and MrLundScience’s channel offered the core guidance that I needed.

The caterpillars hatched from the eggs two days after we received the egg laden milkweed plant in the mail. At first you could not see the caterpillars and only little holes that grew by the hour. Caterpillars go through five instar (or developmental) phases, plus a chrysalis and butterfly formation. With each instar they shed their skin like snakes. By the third instar, they were still tiny and mostly sat still, looking around, and eating. They became finger-sized caterpillars by the fifth instar, and they would work together to greedily devour an entire plant over the course of one night. As they bumbled their way through, one could watch them make decisions about which leaf to eat next, where to chrysalis and, King-Kong style, blindly wave around the front upper half of their body to articulate where they were on the plant or confront another caterpillar. When people talk about these creatures as a symbol for transformation, they are often referring to just caterpillar-to-butterfly. However, I have learned that there are a lot of changes that must happen to become the butterfly and each step warrants respect.

One by one, the caterpillars somersaulted into thee mysterious J hang position (see photo). Despite spinning silk to attach themselves to form their chrysalis, caterpillars do not a spin a cocoon made of silk. Rather a green larval form bursts through their skin, as if from a cheesy science fiction film, resulting in an immaculate green and gold chrysalis. After two weeks, butterflies quickly and quietly creep out of the chrysalis. It’s easy to miss them emerging as they quickly slip out, their wings soft, wet and scrunched. As wings dry, a bloated abdomen pushes out fluid until achieving a slender shape. Everything about this process is gross and deliberate.

Sixteen butterflies populated our apartment. They were fuzzy little creatures that would curiously swivel their heads, unleash spiraling tongues, and would greedily suck up the honey water we fed them. We shared the joy by releasing a few outside a senior center and releasing others with friends in a milkweed filled meadow. The runt of the litter, always the last to instar, was the last one to be released. We feared he might have been dead a few times, after having created the shrimpiest chrysalis we had seen. But, he finally emerged, and, like the others, flew away all on his own.

Photos courtesy of the author.