Crossing Witherspoon Street from the library, the shiny blue tiled Arts Council of Princeton building beckons, a Graves design. Scattered in rooms throughout my home, there’s a small but mighty collection of beautiful everyday objects, practical to use, pleasing to view and to handle. I live with the gift of Michael Graves’ creativity every day. Not a day goes by without my taking a moment to appreciate this man’s work.

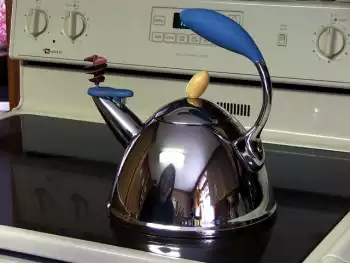

I check the time in my bathroom, where a shelf houses the blue wooden Graves clock shaped like a tiny skyscraper. I look up when I’m cooking or washing dishes. My kitchen cabinets are topped with a collection of teakettles: the blue enamel Mickey Mouse kettle is well worn and a bit scorched by the gas flame, the bird kettle is pristine, and the sports whistle kettle is mint condition. (No surprise– neither is real silver, but they remind me of family times, cups of tea, good memories). Morning toast pops up in my well-loved white Graves toaster, icy beverages whip up in my Graves blender, where the color has chipped from plastic, but the shape of the vessel still makes me smile. My grandmother’s china cabinet holds Graves metal mixing bowls, ladles, and a crazy modern kitchen whisk.

I met Michael Graves twice. The first occasion was the kickoff of his Target product line, one of the chain’s first designer collaborations, here in Princeton. The ad slogan was “Good design should be affordable for all.” Mr. Graves appeared in the campaign ads and was there in person as well, with his Dremel rotary grinder to “autograph” footed metal bowls with spouts and wonderfully ergonomic utensils. He took time to greet and talk to every person in the long line, beaming with enthusiasm and wishing us long and happy use of the objects he’d dreamed up. I remember thinking how approachable this famous architect/designer was, and how tired he would be at the end of the day.

The second occasion was in March, 2013, when Mr. Graves spoke about his life’s work to a lunchtime crowd for a Spotlight on the Humanities program in the library’s community room. The only one from his Harvard graduating class who hadn’t been to Europe, the Rome Prize award allowed him to travel and study architecture, and once abroad he knew he’d “died and gone to heaven.” Every day he picked something to draw thematically (round churches, aqueducts, fountains) in Rome, where he was constantly reminded of the beauty in utility and infrastructure. Talking about renovating his studio, a masonry warehouse built by the Italian stoneworkers who built Princeton University, he compared the transformation to an archaeological dig, unearthing trash and trees and replacing them with pergolas, niches, vaulted ceilings and a fountain in the entry, conjuring his beloved Academy. He studied fine architectural details on classical vessels and objects with a magnifying glass, thinking he’d design handles (flash forward to those Target kitchen utensils and ADA lever handles’ early genesis) and firmed interests in utilitarian projects, big and small. Tables turned proudly on the one-of-a-kind objects like his $25,000 Alessi sterling silver tea set, as Graves designed “American” bird and themed tea kettles, mass produced, attractive and wildly popular, and 2 million everyday shoppers took them home. After his paralysis, his efforts enveloped hospital public and convalescent spaces and aids, to bring design innovations to those in therapy and struggling with everyday life tasks.

From Roman bakers ovens’ round portals to Amsterdam house skylights, from cutlery to grand scale hotels, Michael Graves showed us how to look at the world differently, with purpose balanced against gentle whimsy, colorful surprising shapes, humor and humanity. Every day I appreciate these gifts.

Photo attribution: stefernie on FLICKR, via Creative Commons license